Native Americans in North America celebrated harvest festivals for centuries before a Thanksgiving federal holiday was formally established in the United States. Colonial services for these festivals date back to the late 16th century. The autumnal feasts celebrated the harvest of crops after a season of bountiful growth.

In the 1600s, settlers in Massachusetts and Virginia held feasts to express gratitude for survival, fertile fields, and their faith. The Pilgrims in Plymouth, Massachusetts, had their Thanksgiving feast in 1621 with the Wampanoag Native Americans.

This 3-day feast is considered the ”first” Thanksgiving celebration in the colonies. However, there were other recorded ceremonies of thanks on these lands. In 1565, Spanish explorers and the local Timucua people of St. Augustine, Florida, celebrated a mass of thanksgiving. In 1619, British settlers proclaimed a day of thanksgiving when they reached a site known as Berkeley Hundred on the banks of Virginia’s James River.

Of course, the idea of “thanksgiving” for the harvest is as old as time, with records from the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Native American cultures, too, have a rich tradition of giving thanks at harvesttime feasts, which began long before Europeans appeared on their soil. And well after the Pilgrims, for more than two centuries, individual colonies and states celebrated days of thanksgiving.

How Did the Pilgrims Come to Settle Here?

When certain men and women of Scrooby, England, were persecuted for separating themselves from the Church of England, they, as Pilgrims, fled to Leiden, Holland. Upon the execution of separatist leader James of Barneveld there on May 13, 1619, they realized that Holland was no freer than England and prepared to go to America.

On July 20, 1620, after putting their plans into effect, they asked for the parting words of their beloved pastor, John Robinson. The next day, they boarded the ship Speedwell, anchored where the canal from Leiden entered the Maas (or Meuse, a river flowing into the North Sea) at Delfshaven, and sailed for Southampton, England.

After misadventures and more farewells, these 102 brave souls departed on the Mayflower on September 6, 1620.

The Mayflower arrived at what is now Provincetown, Massachusetts, at the tip of a curved peninsula later named Cape Cod, on November 21 and, on that day, drew up one of the most significant documents of American history, the Mayflower Compact. The Compact was a constitution formed by the people—the beginning of popular government.

They then explored the lands along the bay formed by the peninsula. On December 22, after holding the first town meeting in America to decide where to build their homes, the Pilgrims went onshore at a site now called Plymouth Rock. There, on the shore above the rock, they settled. After 400 years, their descendants and those of the Puritans are still sailing along.

What Ever Happened to the Pilgrims?

So, whatever happened to the Pilgrims? The following highlights reveal what has transpired for the Pilgrims, their Puritan contemporaries, and the descendants of both.

- 1621: Over dinner with some of their Native American guests, they gave thanks for their welfare

- 1621: Built a meetinghouse

- 1634: Forbade wearing gold and silver lace

- 1639: Started a college (Harvard)

- 1640: Set up a printing press

- 1647: Hanged a “witch” (Alse Young—the first person to be executed for witchcraft in the Thirteen Colonies)

- 1704: Printed the first newspaper in Boston

- 1721: Were inoculated against smallpox

- 1776: Again declared themselves to be free and independent

- 1792: No doubt purchased the 1793 first edition of Robert B. Thomas’s Farmer’s Almanac. Today known as The Old Farmer’s Almanac, this book is North America’s oldest continuously published periodical.

The First National Thanksgiving Proclamation

The first national Thanksgiving celebration was observed in honor of the creation of the new United States Constitution! In 1789, President George Washington issued a proclamation designating November 26 of that year as a “Day of Publick Thanksgivin” to recognize the role of providence in creating the new United States and the new federal Constitution.

Washington was in his first term as president, and a young nation had just emerged successfully from the Revolution. Washington called upon the people of the United States to acknowledge God for affording them “an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.” This was the first time Thanksgiving was celebrated under the new Constitution.

Thanksgiving’s Path to a Federal Holiday

While Thanksgiving became a yearly tradition in many communities—celebrated on different months and days that suited them—it was not yet a federal government holiday.

John Adams (second U.S. president) and James Madison (fourth U.S. president) issued proclamations recommending such observances as a “National Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer” or a “Day of Public Thanksgiving for Peace.” Thomas Jefferson (third U.S. president), however, believed in the separation of church and state and that the federal government should not have the power to dictate when the public should observe a religious demonstration of piety, such as a national day of thanksgiving.

In a private letter written to Rev. Samuel Miller in 1808, Jefferson wrote: “I do not believe it is for the interest of religion to invite the civil magistrate to direct its exercises, its discipline or its doctrines: nor of the religious societies that the General government should be invested with the power of effecting any uniformity of time or matter among them. Fasting & prayer are religious exercises. The enjoining them is an act of discipline. Every religious society has a right to determine for itself the times for these exercises & the objects proper for them according to their own particular tenets; and this right can never be safer than in their own hands, where the constitution has deposited it.”

While religious Thanksgiving services continued at a local or state level, after Madison no further presidential proclamations marked Thanksgiving until the Civil War of the 1860s.

Thanksgiving Becomes a Federal Holiday

It wasn’t until 1863, during the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a national Thanksgiving Day to be held each November.

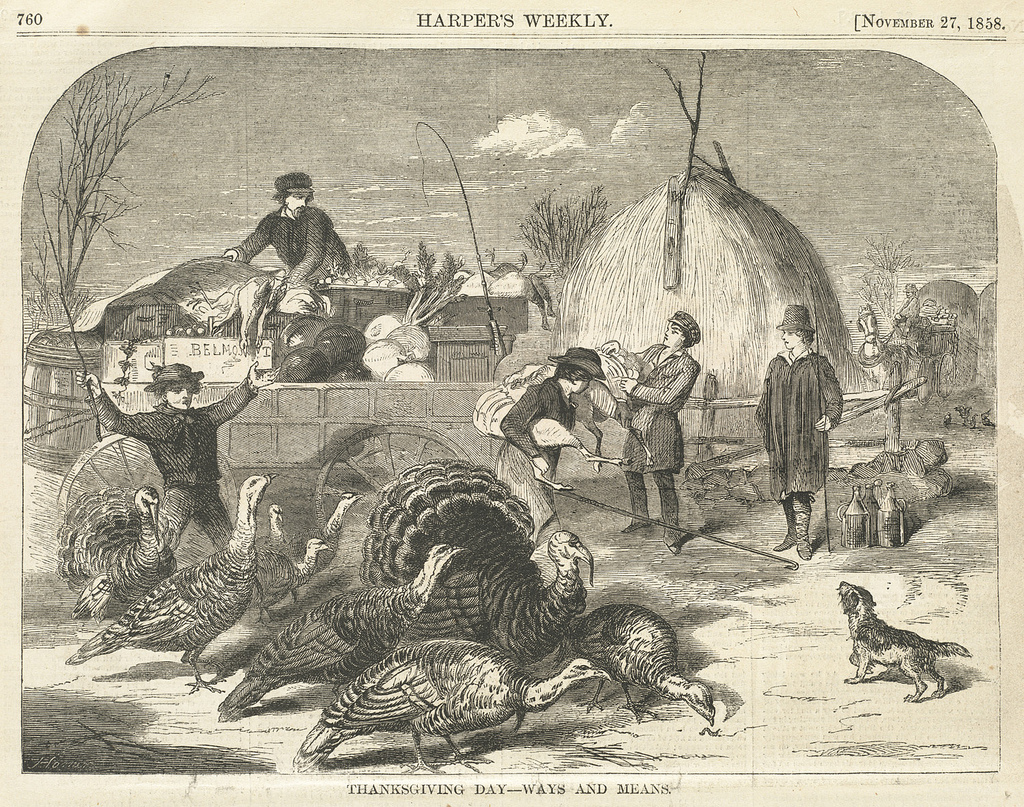

Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

In addition, President Lincoln proclaimed Thursday, November 26, 1863, as Thanksgiving. Lincoln’s proclamation harkened back to Washington’s, as he also thanked God following a bloody military confrontation.

Lincoln expressed gratitude to God and thanks to the Army for emerging successfully from the Battle of Gettysburg. He enumerated the blessings of the American people and called upon his countrymen to “set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise.” As of that year, Thanksgiving was celebrated on the last Thursday in November.

Thanksgiving is briefly moved to the third Thursday in November.

In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt changed Thanksgiving from the last Thursday in November to the second to the last Thursday. It was the tail end of the Depression, and Roosevelt’s goal was to create more shopping days before Christmas and boost the economy. However, many people continued to celebrate Thanksgiving on the last Thursday in November, unhappy that the holiday’s date had been meddled with. You could argue, however, that this helped create the shopping craze known as Black Friday.

In 1941, to end any confusion, the president and Congress established Thanksgiving as a United States federal holiday to be celebrated on the fourth Thursday in November, which is how it stands today!

Of course, Thanksgiving was not born of presidential proclamations. Read about Sarah Josepha Hale, the “Godmother of Thanksgiving,” who helped turn this historic feast into a national holiday.